There is an interesting clash between giving free speech to every student and limiting that speech within the public and private school sectors. As an arts teacher, I am continually thankful that the First Amendment protects the right to free expression, however, this rights is not absolute and may be limited. Schools are one of the most potent examples of where First Amendment limitations can be found because there is a compelling interest in maintaining an appropriate educational environment. Teaching theatre, I continually keep this in mind when I select a production – due to copyright laws we can’t alter the content, so we need to fully accept it as it is.

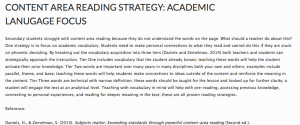

The Supreme Court has established that schools have the authority to regulate student speech in order to maintain an appropriate educational environment. In Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), the court established the “Tinker standard,” which states that schools may only regulate student speech if it will substantially disrupt the educational process or invade the rights of others. Where do disruptions to occur? The content of a play can be disruptive or inappropriate for all viewers. Many early theatre makers or non-theatre-school-administrators, can be tempted to alter the text of a play (e.g. switching out a swear word or changing any words to effect a character interpretation).

The Tinker standard was increasingly defined in Morse v. Frederick (2007), the court held that schools may prohibit student speech that promotes illegal drug use, even if it is not disruptive. This expanded the power of schools to regulate speech. The cascading impact of this is that the content of what a school chooses to present in their arts programs. This could be a concern in the arts because the arts are founded on free speech; their power rests in the ability to take on a wide range of topics and create conversation within the community. Arts can change the world but they need the forum to do so. Though, one could argue that the voices on topics not ready for school can wait for a venue outside of graduation – these are also the voices of the future and the students that I work with are talented, trustworthy, insightful, and thoughtful. It’s an interesting line to respect and work with as an arts administrator.

By contrast, private schools are not bound by the First Amendment, as they are not government institutions. However, many private schools have policies in place that protect the free expression rights of their students, and these policies may be enforceable under state law.

Venues outside of graduation are not the only avenue for student expression. In Mahanoy v. B.L. (2018), the court held that a school cannot punish a student’s off-campus speech, even if it is disruptive to the educational process, unless the school can demonstrate that it has a reasonable expectation of the speech reaching the school environment. Students could use their free expression, within the arts, outside of the school gates.